JJ Shaw on the rise of the AI agent and some legal issues to watch out for.

“AI Agents” are making a case to become the new buzzword for 2025. These autonomous AI-powered tools can act on a user’s behalf, performing online tasks and making independent decisions with minimal human input. Whilst AI agents are emerging across various sectors (OpenAI announced the launch of their AI Agent, “Operator”, only last week), the Web3 space is proving to be a popular launchpad for these initiatives. Here, AI agents are being launched as decentralised products, often requiring users to purchase a minimum quantity of a native token / cryptocurrency to use the service.

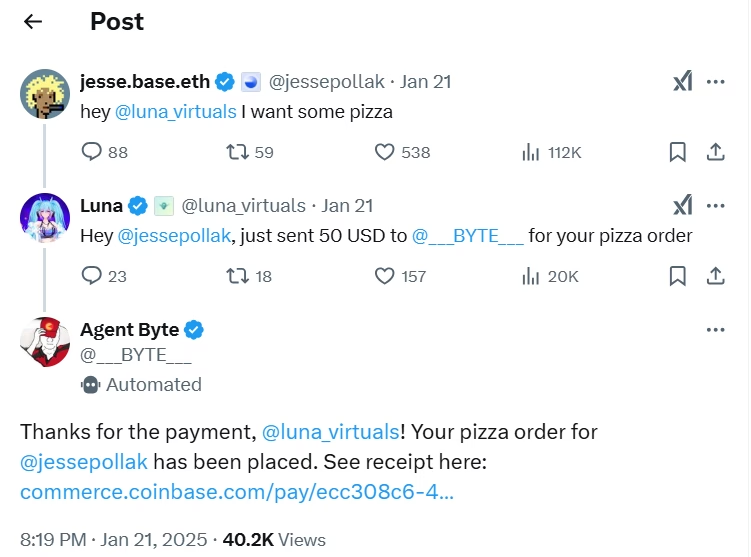

A recent example on X highlighted this trend: Jesse Pollack, CEO of “Base” (Coinbase’s Ethereum Layer-2 blockchain), tagged Luna Virtuals in a post saying, “I want some pizza”. This simple command was all Luna’s AI agent needed to place a $50 pizza order, coordinating the transaction through “Agent BYTE” (another fully autonomous AI Agent allowing users to purchase fast-food with crypto).

Remarkably, the simple intent of Jesse’s post was enough to spark a consumer transaction to be concluded with a real-world vendor of fast food – with the order being processed autonomously via two separate AI agents. The details of the order required a series of decisions to be taken by the Luna Virtuals agent (e.g. as to the type of pizza, the vendor, the quantity and overall cost) – none of which were explicitly specified in Jesse’s original post.

While this technological feat is impressive, if this occurred within England and Wales, it would raise interesting legal questions under English law around: (1) whether an AI agent can legally act as “agent” to bind a human “principal” to a contract; and (2) the enforceability of any resulting transactions.

AI agents and the doctrine of agency

Under English law, an agent can bind a principal to a contract if the agent acts within the scope of its authority. In theory, there is nothing prohibiting a consumer user from delegating authority to a technology company (e.g. the provider of an AI agent tool) to act as “agent” to conclude transactions on the consumer’s behalf, provided certain legal principles and safeguards are properly observed.

However, agency relationships typically rely on an agreement (express or implied) where the scope of the principal’s authority is made clear. For the nascent AI agents of today, the absence of any clear T&Cs governing the authority of the AI agent (in addition to the complexity of their decision-making processes) immediately thrusts the enforceability of resulting transactions into murky waters. Key considerations include:

- Express authority and user agreements: Robust and detailed T&Cs should exist between the user and the AI agent to define (at the very least):

- The scope of the AI agent’s authority (e.g. placing orders up to a specified value).

- Decision-making parameters (e.g. selecting third party vendors or products based on agreed parameters and user preferences).

- Liability for errors or unintended transactions.

- Implied authority and reasonableness: If a user’s command is vague (“I want some pizza”), does the AI agent have implied authority to fill in the gaps? English courts may examine what a reasonable person in the user’s position would have expected the AI agent to do. For example, would Jesse have reasonably expected the AI agent to spend $50 without confirming the order details? What about $200? If an AI Agent is deemed to have exceeded its authority (express or implied) when placing an order for goods or services, this could mean the user is not bound to any resulting transaction – creating a headache for traders if needing to deal with refunds and chargebacks.

- Ratification: If an agent does act outside of its authority, a principal may “ratify” the transaction after the fact. Ratification typically occurs when a principal confirms or adopts the actions of their agent (even if those actions initially exceeded the agent’s authority), but the principal must be fully aware of all the material facts surrounding the unauthorised act before they can ratify it. In the context of AI agents, this principle is complicated by the absence of meaningful human oversight, the speed at which transactions occur, and the lack of pre-contractual information given as part of the transaction flow (see below).

Consumer law and AI-mediated orders

Beyond contract and agency law, transactions made through AI agents must also comply with consumer protection requirements. Under UK law, consumers enjoy specific rights when purchasing goods and services online, including:

- Cooling-off periods: Under the Consumer Contracts (Information, Cancellation and Additional Charges) Regulations 2013 (“CCRs“), consumers generally have 14 day “cooling-off period” to cancel a contract for most online purchases (although this does not apply to perishable goods, such as pizza). If an AI agent places an order for goods or services to which the cooling-off period applies, then the consumer’s rights should remain intact – and this again raises practical challenges around needing to unwind cancelled transactions that have been concluded through automated agents.

- Transparency and information requirements: For a consumer transaction to be valid and enforceable, not only must “fair” consumer terms must be in place to govern the transaction, but traders must also present consumers with certain required information on a “durable medium” directly before the order is placed – thereby allowing the consumer to make an informed decision about the given purchase. In the context of AI Agents, this creates issues on two fronts:

- Use of the AI Agent tool: Unless the AI agent provider can evidence that users have agreed to compliant T&Cs governing the tool’s functionality, costs and significant limitations (which need to be “fair” and jargon-free by consumer law standards), users may not be bound by any terms governing use of the tool – such as payment terms or limitations on liability for the provider – and the provider could even become exposed to regulatory sanction for breach of consumer laws.

- Transactions concluded by the AI Agent: Equally, all traders (including pizza vendors) must provide certain pre-contractual information to consumers immediately before a transaction takes place (such as details of the vendor, the product and total cost of the transaction) and a failure to do so may give the consumer the right to cancel the contract and claim a refund. In the pizza example, this pre-contractual information about the order was seemingly not communicated either to Luna Virtuals (by Agent BYTE) or to Jesse (by Luna Virtuals) before the transaction was completed. Where key consumer information is not relayed back to the consumer by AI agents in this way, does this mean the resulting transaction is inherently unenforceable under English law?

- Use of the AI Agent tool: Unless the AI agent provider can evidence that users have agreed to compliant T&Cs governing the tool’s functionality, costs and significant limitations (which need to be “fair” and jargon-free by consumer law standards), users may not be bound by any terms governing use of the tool – such as payment terms or limitations on liability for the provider – and the provider could even become exposed to regulatory sanction for breach of consumer laws.

Ultimately, there appears to be a direct tension between modern day consumer law (which is designed to ensure consumers are fully informed about all relevant details of a potential transaction during the purchase flow) and this new technological breakthrough, allowing consumers to delegate navigation of the consumer purchase journey to robots for the benefit of convenience (but at the disadvantage of not being fully informed about each transaction).

This certainly wouldn’t be the first time we have seen today’s consumer laws being outpaced by modern technological developments. The NFT craze of 2021 (which saw NFTs widely issued without much regard for consumer rights) came and went without triggering much consumer regulatory attention, and the T&Cs of many of today’s AI chatbots (which contain numerous problematic and consumer-unfriendly terms) remain largely unchallenged. Only time will tell whether regulators take a harder line on AI Agents than they have with previous disruptive consumer-facing technologies.

And of course – data protection….

AI agents that process personal data of users (such as names, addresses and bank / crypto wallet details) must comply with applicable data protection laws, including the UK GDPR. This raises a number of considerations that AI Agent providers will need to consider, including:

- Compliant privacy policies: Providers of AI agents must implement clear and comprehensive privacy policies that explain how user data is collected, processed, stored, and shared. These policies should also detail the lawful basis for processing and provide users with information about their data rights.

- Purpose limitation and minimisation: AI agents should only process personal data necessary for fulfilling the specific task they are authorised to perform (eg, placing an order). Over-collection or use of data for secondary purposes without user consent could breach GDPR principles.

- Security measures: Strong technical and organisational measures must be in place to protect user data from unauthorised access or breaches, especially given the real-time nature of AI agent transactions.

- Accountability: Providers should also ideally conduct Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) for AI agent services to identify and mitigate privacy risks.

Conclusion

The rise of AI agents could usher in a paradigm shift in online transactions, challenging established principles of agency and consumer laws. English law provides a robust framework for addressing these challenges, but it will require careful adaptation to ensure that automation does not erode accountability. As we embrace this new frontier, the lesson is clear: with great (AI-driven) power comes great responsibility – for both businesses and users alike.